The Greater Prairie-Chicken

The Grouse of the Tall Grass Prairie

Ann Jandernoa

May 20, 2022

The Greater Prairie-Chicken “Booming on the Prairie”

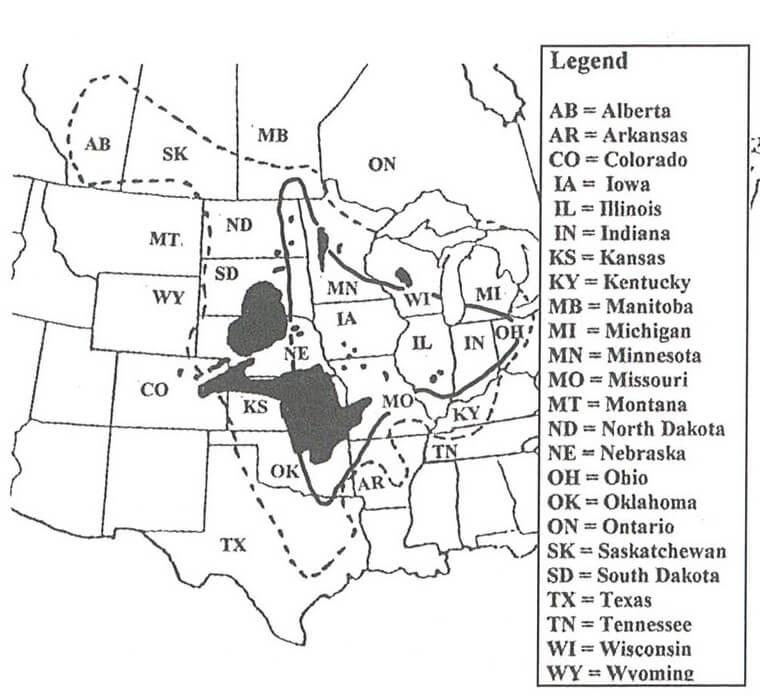

The Greater Prairie-chicken was once widespread in North America, ranging from central Canada to Texas, and included three distinct subspecies. The Heath Hen is now extinct, and the Attwater numbers are critically low.

The air sacs are called tympani, which is Latin for kettle drums.

In 1855, prairie-chicken population was approaching an all-time peak, between 10 and 12 million birds.

Meat hunters would ship the birds to Chicago by the trainload. The birds were stacked and sold by the cord and ton. The hunters received approximately $3,75 per dozen birds.

It has been documented that at least 600,000 birds were shipped to market in Chicago per year.

Greater Prairie-Chicken hunting in Kansas by Theodore R Davis late 1800’s

The Decline of the Greater Prairie-Chicken’s Range

Historically the Greater Prairie-Chicken has been documented to have occurred in 20 states of the United States and four Canadian provinces; however, they are now located in 11 states and are extinct from Canada.

The map to the right illustrates the original range of the Greater Prairie-Chicken in North America in the past (dashed line; adapted from Schroeder & Robb 1993) and at present (solid areas; adapted from Westemeier & Gough 1999. The solid line delineates the approximate pre-settlement boundary of the tall grass portion of the prairie biome (adapted from various sources).

Status and management of the greater prairie-chicken Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus in North America W. Daniel Svedarsky, Ronald L. Westemeier, Robert J. Robel, Sharron Gough, John E. Toepher

Greater Prairie-Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus), located on the Bluestem Prairie Reserve, Minnesota, USA

Range and Habitat Density Maps

To the right are two maps.

The map on the left indicates the current range of these birds.

The map on the right identifies the potential areas that have denser numbers of birds.

Compare the photos of Greater Prairie-Chicken habitat and range and you can determine how little prime habitat is left for this bird to survive in.

In reality, the density is a direct correlation to the availability of prime habitat.

These two maps will help you understand the difference in the range of the Greater Prairie-Chicken and how much prime habitat is actually available to this species to utilize within the range.

These maps were created by TheCornellLab

What is a Lek?

“leks” is Swedish for dance.

Leks are also called dancing grounds. These areas are mostly flat with short grass, typically under six inches. Sometimes a burned area or cultivated lands, hilltops, and occasional wetland meadows are suitable as a lek site.

Lek size 50 to 100 yards diameter

If the grass around and on the lek becomes too tall, the site may be abandoned. Too much shrub around the lek will also decrease the use of a site and eventually will be abandoned.

The Greater Prairie-Chicken chooses a lek site that is slightly elevated, flat ground, having short grass with a good field of view. In other words, the males want to be seen and know when a female arrives while being on the lookout for predators.

Peak lek time for males ranges between March to May. However, the females typically start visiting the leks in April.

Males have specific territories on a lek site where they display for the females. The prime areas of a lek are in the center areas. Dominate males will be located, and less dominant males will be located on the fringes of the lek.

The males will fight, jumping up in the air and using their talons as a fist to attack the other male.

The Competition is Fierce on the Dancing Grounds

The male will erect the pinnae feathers above his head. He will then inflate the air sacs on the side of his neck, and lowers his wings, all while he will be rapidly stomping his feet and making calls (booms).

The male will also make a series of crows, calls, and cackling noises while displaying.

The male will also do short vertical flights called “flutter-jumps” which often occur in conjunction with booming. When a female is near, the male may perform a nuptial bow with wings spread, pinnae erect, and bill lowered to the ground.

The more dominate the male the greater the chances to be chosen for breeding. The hens tend to prefer the more dominant males.

Female Greater Prairie-chickens start visiting and mating at lek sites a few weeks after males have begun displaying and have established their social hierarchy at a lek site.

The females will walk through the center of the lek site, checking out the mating males. This walk is done to identify the more dominant males defending their territories within the lek site.

One of the main problems with a low population of Prairie-chickens and the female’s tendency to only choose the dominant males is that this decreases genetic diversity. This will result in inbreeding which can weaken the overall health of a population.

A Prairie Blessing sign on a barbwire fence located on the prairie of the Flint Hills of Kansas.

The Greater Prairie-Chicken needs the Prairie in order to Survive

The major threats to Greater Prairie-chicken populations are the loss,

fragmentation, and degradation of habitat on both private and public lands which occur through the following:

Some of the causes of loss of habitat

- Livestock grazing and overgrazing areas

- Loss of Parries grasslands crop production and development

- Burning of Pasture lands and Grasslands

- Use of pesticides and other chemicals

- Loss of nesting and brood-rearing habitat areas

- Small populations and the problem of lack of genetic diversity

The Greater Prairie-chicken is very sensitive to habitat fragmentation. Breeding populations typically require greater than 185 acres of unfragmented prairie habitat.